Production is production – how can it be lean? The debate about what exactly lean production is and isn’t having been raging since the late 1980s.

The evolution of lean production

John Krafcik was the first to coin the term “lean production” in his highly regarded 1988 article “Triumph of the Lean Production System”. To understand the benefits of lean production and why it has changed the world, we need to know more about it than just its principles and origin. We have to also take into account how industrial production has operated over almost a century.

We are going to examine this topic in two blog articles. The first part looks at the time before lean production and the second, which will appear subsequently in this blog, focuses on the lean philosophy as an alternative to centrally planned production, which was efficient to a certain extent, but not lean.

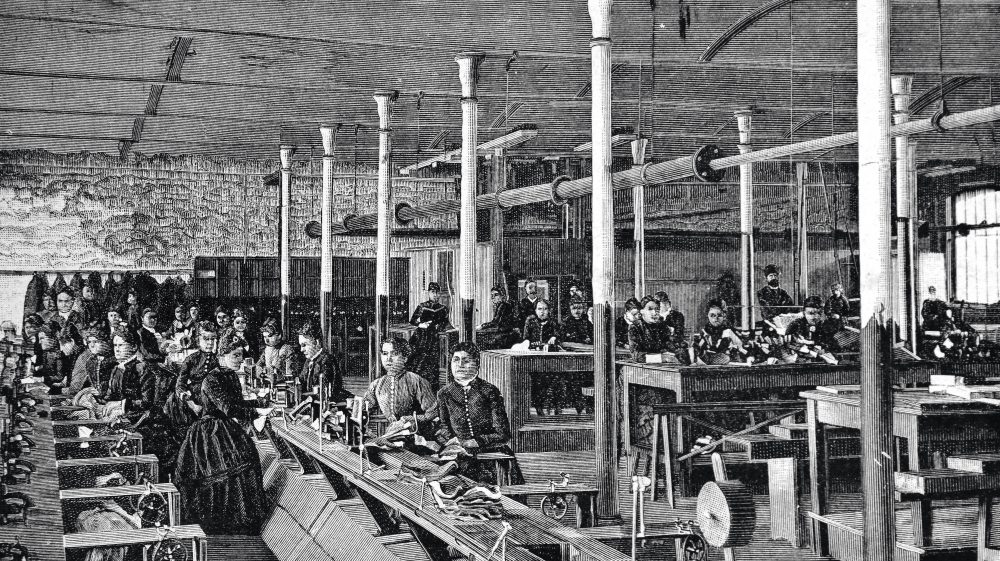

Taylorism – before lean production

An approach that is typical of Taylorism is to divide work processes into separate steps so that each can be centrally planned and optimised. Everything is precisely measured and analysed, such as how long it takes a worker to move a workpiece from the ground to a shelf. All this data is also used to analyse how specific processes can be made more efficient, so that a work bench can be restocked with materials at the same rate that they are being processed, for example. Everything is secondary to the overarching process. Deviations are undesirable – in fact, all the work steps are intended to interlock like gearwheels.

The conveyor belt as a feature of centralised production

In 1913, Henry Ford kick-started the most intense phase of the second industrial revolution when he introduced the concept of focussing consistently on processes. The conveyor belt became a symbol of the industrial age. Conveyor-belt production, standardised mass-market products and specialised machinery were seen as the best ways to drive down costs even further and make products affordable for more and more people.

The conveyor belt set the pace that all other processes had to follow. Deviating from the central plan was not an option – employees were to carry out only the one task from the entire process that had been assigned to them and do so quickly and carefully. Initiative was not encouraged.

However, some ten years after conveyor belts had revolutionised production forever, the first problems started to appear. While customers were increasingly demanding cars that were different, Henry Ford insisted in his book “My Life and Work” that: “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants, so long as it is black”.

The manufacture of variants and ever shorter product cycles posed major challenges for the system of centrally planned mass production. When everything runs as planned, goods can be produced with maximum efficiency, but every change – and therefore every innovation – drives up costs.

Centralised planning and optimisation

Centralised process control reaches its limits when products and markets start to change rapidly. When operating a centrally planned system, making changes is a long, drawn-out and complicated process. Because the system needs to be planned as a whole, production is inflexible. That presented an opportunity for lean production, which we will be looking at in the second part of this article.