Having already introduced you to value-stream mapping, the next step is to take a look at value-stream design.

Let’s start with a quick summary of value-stream mapping from the world of lean production. It involves examining production processes to identify the ones that don’t contribute to value creation and therefore lead to waste. The next logical step is value-stream design – a process language for modelling flows of materials and information that is used to design future value streams. Whereas value-stream mapping records the actual state of production processes, the result of the subsequent value-stream design step is an optimised target state with the shortest possible throughput or lead times. Accordingly, value-stream design always aims to optimise the existing situation. Incidentally, throughput relates not just to production, but also – and most importantly – to the waiting time between processes or during storage. Value-stream design delivers further benefits for the entire process. For one thing, it means shorter delivery times for customers. For another, inventories are smaller, which ties up less capital and means more production space is available. Without having to expand their premises, companies can create additional productive areas and thus generate healthy sales growth. How do you actually go about designing value streams and achieving a tangible improvement, though?

The world of lean production

Less waste and more added value – lean production methods help you make targeted improvements to your production efficiency. Our white paper provides a concise introduction.

DOWNLOAD NOW

Constant focus on optimisation with lean production – how to design value streams

Value-stream design always consists of two steps. The first step is to establish the target situation and the second is to plan the associated improvements. The target situation can also be interpreted as a collective vision, in the sense that the team develops an enhanced, customer-oriented material and information flow. Larger improvement projects (= Kaikaku) and smaller experiments with Kaizen / the PDCA cycle are both incorporated in the planning. The guidelines for designing value streams are as follows:

1.) Divide value streams into segments

Generally speaking, non-segmented value streams result in greater complexity and additional outlay when it comes to business planning and management. Segmentation divides production into product families. In other words, products that undergo similar process steps are regarded collectively – in the product family’s value stream. This optimisation makes it possible to achieve more efficient material and production flows. That’s why it’s always better to divide different value streams into separate segments.

2.) Produce to a planned takt time

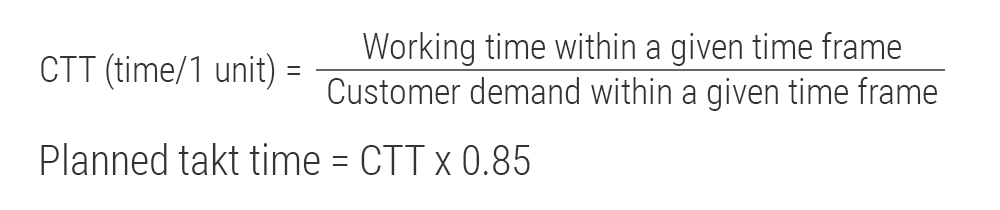

When it comes to designing value streams, knowing both the customer takt time and the planned takt time is vital. These two takt times create the basis for the target state and, amongst other things, determine the cycle time and the number of employees used. The planned takt time is calculated from the customer takt time. As a rule of thumb, it is 15 percent faster. The equations for the customer takt time (CTT) and the planned takt time are as follows:

3.) Pull instead of push

Reducing the waiting time between the various process steps offers the greatest potential for shortening the throughput time. With the conventional push approach, waiting times often account for over 90 percent of the total throughput time, so the key is to switch production from push to pull, if possible. Production traditionally follows the push principle, meaning that sales figures are analysed and used to draw up forecast-based production plans. The actual customer order is not a factor. With the pull principle that is typical of lean production, on the other hand, a workstation will only deliver its output when this is requested by the next station downstream or a customer. There are various ways of incorporating production appropriately into the flow, all of which are based on the pull principle – one-piece flow, FIFO (first in, first out) and Kanban:

a) One-piece flow (OPF): Unlike batch production, with one-piece flow, the workpiece “flows” through the production process without stopping along the way. The workstations are often arranged in a U-shape (= OPF cell). The rabbit chase system or the sequence principle is commonly used for the OPF cells. With the rabbit chase system, all staff carry out all work steps, which optimises capacity utilisation and eliminates waiting times. However, it also means everyone has to be trained for all work steps. The sequence principle, on the other hand, has the advantage that an employee only performs certain work steps and, accordingly, only needs to be trained for these steps. Staff don’t work to optimum capacity, though, especially since waiting times are likely. Throughput times and stock levels are lowest with one-piece flow because there is no interim buffering. This method should always be used where possible.

b) FIFO: If using one-piece flow to improve production doesn’t work, FIFO buffers are a good idea. With the FIFO method, parts in a value-added chain that were produced first also undergo further processing first. This results in low storage costs. Avoiding long storage periods also significantly reduces any loss of quality in the materials. Buffering a smaller number of different products keeps throughput times and stock levels low. Only products that have been ordered are buffered, and in precisely the same sequence as they were ordered.

c) Kanban: If neither one-piece flow nor FIFO works, use Kanban to uncouple the process. Kanban (a Japanese word meaning “signboard” or “billboard”) enables information – especially regarding needs-based material requirements – to be continuously passed back and forth between the stations in a production system. If an assembly station needs a certain part, this is taken out of storage and its Kanban card is sent to the upstream station to request that another of the same part is supplied. Essentially, that makes the relevant downstream process the “customer” of the upstream process. Kanban is also known as the “supermarket principle”, as it is based on the restocking of goods in supermarkets.

4.) Correctly incorporate production orders

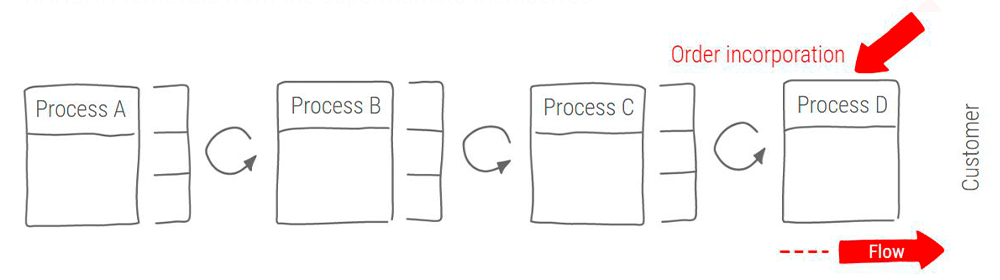

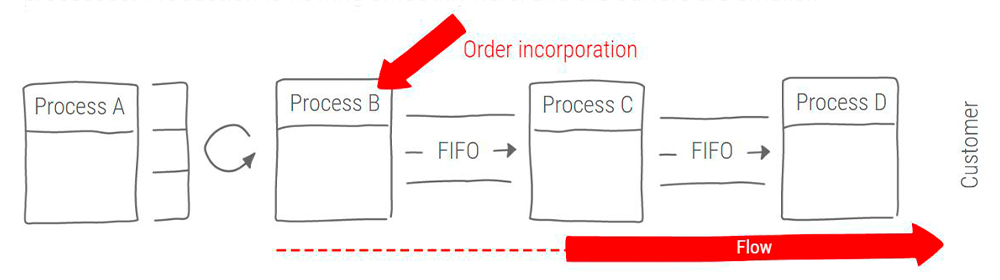

“Incorporate” means creating a production order. Coming into play at the point when this production order is incorporated, the “pacemaker process” determines the rhythm for all upstream and downstream processes. It also changes the type of production – from a customer-independent system to an order-specific one. There are two different approaches to order-specific production:

Late order incorporation: Orders are incorporated during the final process, so process D is the pacemaker in this case. With the push principle, order incorporation takes place separately for each and every process. With the pull principle, on the other hand, it’s always just one single process – i.e. the pacemaker – that controls all the processes. Upstream processes control themselves based on the Kanban removals from the supermarkets.

Early order incorporation: Process B is the pacemaker in this case, controlling all upstream and downstream processes. That makes for a smooth production flow and smaller buffers.

5.) Levelling and smoothing

In the pacemaker process, the Heijunka method is used to level and smooth out the production schedule. In the lean production context, levelling means dividing production into daily quantities, while smoothing repeats the production cycle several times a day. The aim of repeated smoothing is to create a production model that gets as close as possible to a batch size of 1. Heijunka requires brief and frequent changeovers to accommodate smaller batch sizes, right down to a batch size of 1.

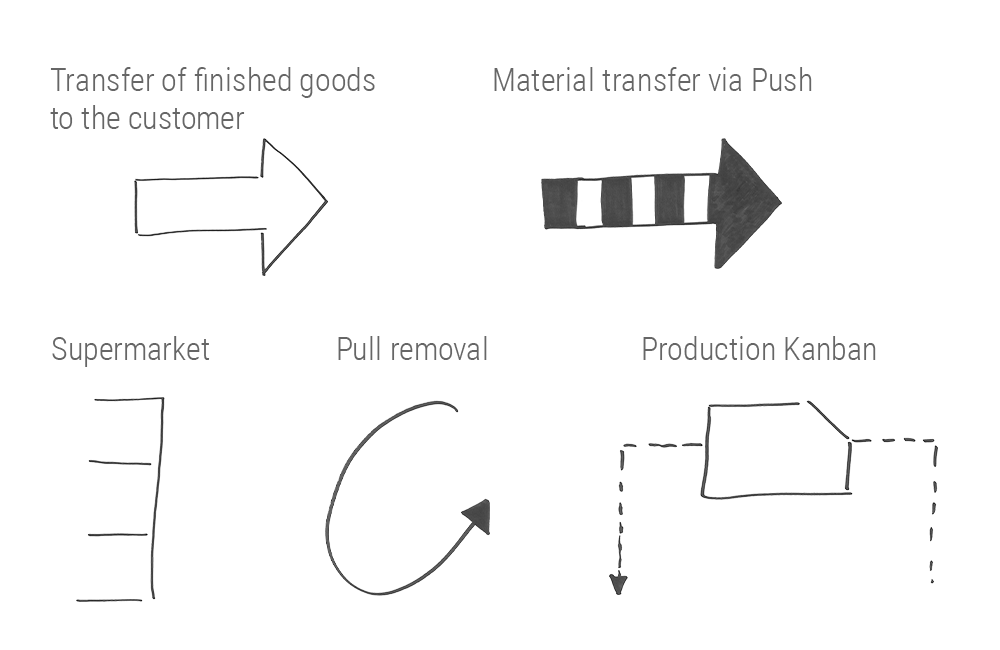

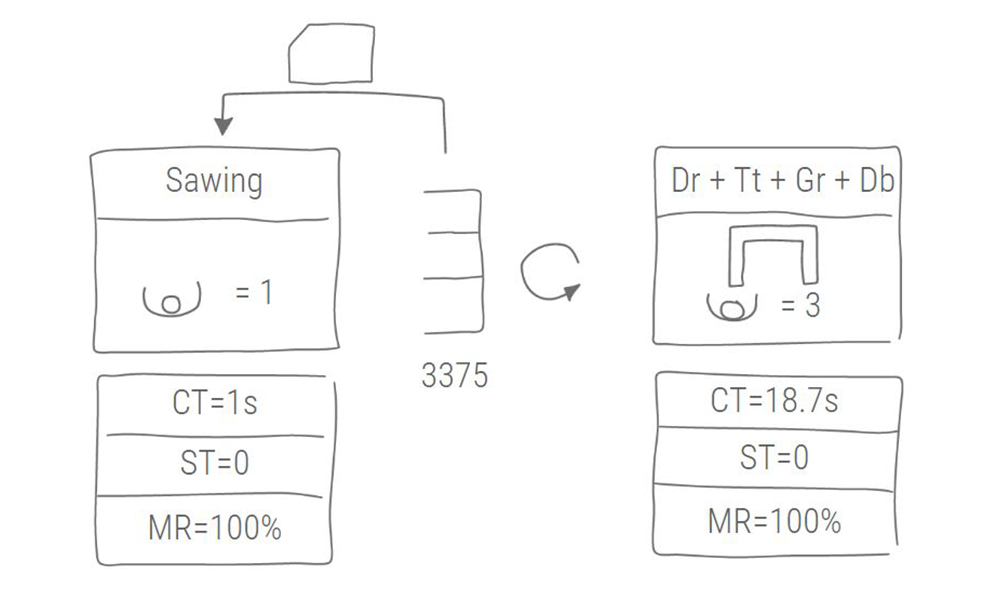

Value-stream design – symbols depicting the value streams

Established value-stream symbols are used to model value streams. These symbols are a fundamental part of designing value streams. Would you like to discover exactly how these symbols are used? You can gain more in-depth knowledge by working through the online training module on value-stream design in the item Academy. Modules relating to value-stream mapping, further lean production methods and many other industry-related topics are also available. All you need to access the item Academy and the full range of other digital services item offers is a free item user account.

Besides additional information about the concepts covered in this blog post, you will also find practical tasks. For example, you can check whether you have calculated the customer takt time and planned takt time correctly. The module ends with a task calling for you to define the target state with the help of value-stream design, based on the value-stream diagram for a fictional actual state that we included in our recent blog post about value-stream mapping.

Here are a few basic value-stream symbols to get you started:

This section from a model clearly shows how value streams are structured:

Are you interested in fascinating reports and innovations from the world of lean production? Then we have just what you’re looking for! Simply subscribe to the item blog by completing the box at the top right.